Lygia Clark's work is considered multiple, complex, and challenging. Her career encompasses crucial changes in the art of the second half of the twentieth century: besides being a pioneer in the development of geometric abstraction in Brazil, which would give rise to the Neo-Concrete movement, Clark demonstrated, from the outset, a concern with painting as an object, and with its relationship with real space.

Lygia Clark showed an interest in drawing from an early age, and began her studies in the late 1940s, under Roberto Burle Marx. In the early 1950s, she settled in Paris, where she studied oil painting under Árpád Szenes and Fernand Léger and presented her first solo show in the city in 1952. Back in Brazil, Clark embarked on an intense dialog with the generation of artists who were approaching geometric abstraction. During this period, Clark took part in exhibitions with the Grupo Frente, and exhibited at the Venice Biennale (1954) and several editions of the Bienal Internacional de São Paulo.

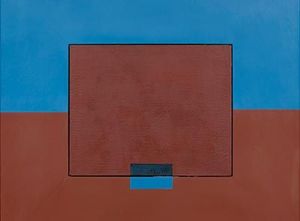

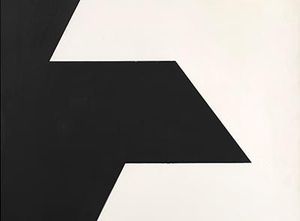

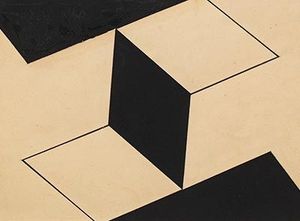

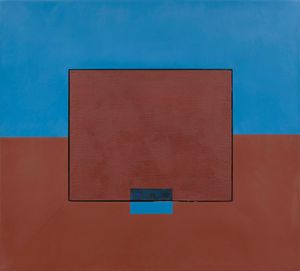

The celebrated series Planos em superfície modulada (Planes on Modulated Surface) illustrates Clark’s development of the organic line. Conceived from the observation of functional lines used to modulate and articulate surfaces in everyday objects - the line between door and wall, lines on sewn fabrics or the space between floorboards - the organic line consists of an element that structures the picture by means of an articulation of polarities: light/dark, positive/negative, inside/outside. In these studies, Clark experimented with various possibilities of modulating space with the use of collage. These works on paper were conceived as blueprints for her paintings, usually made with industrial paint which she applied with a spray gun on wood.

In the 1950s and 1960s, Clark took the steps that lead her to a radical investigation of the boundaries between art object and space, and between the work and the viewer. Gradually, her interest turned to three-dimensionality. With Casulo, she created reliefs that emerged from paintings, and made sculptures and objects out of industrial materials, such as the Trepantes. Her next step was to break down the separation between artistic objects and the public. Lygia created Bichos, mobile structures made of sheet metal and hinges that must be manipulated by viewers. From then on, her production was based on the idea that the artist is a proposer of situations. She began to propose happenings and performances that required the participation of the public, such as O Eu e o Tu: Série Roupa-Corpo-Roupa (1967) or immersive installations with a strong psychological and symbolic charge, such as A Casa É o Corpo: Labirinto (1968).

In the last decade, Clark's work has been the subject of retrospectives at international institutions such as MoMA and the Guggenheim, in a process of increasing appreciation of his career, which goes hand in hand with the inclusion of his works in major collections, including Tate; MoMA, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Center Pompidou and Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros. His work is included in the collections of the main Brazilian institutions, including the Pinacoteca de São Paulo, Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo, Museu de Arte Moderna do Rio de Janeiro, Instituto Inhotim, among others.